Do we need 'emergency money’? This question is a very legitimate question! What is 'emergency money', what are its effects and why should similar alternatives be used from time to time? Indeed, as they say, history repeats itself, and so from time to time the 'old tried and tested solutions' come up!

From time to time, economic crises bring the need for alternative currencies to the surface. Although digital solutions are nowadays in the spotlight, there have been many occasions in history when emergency money, i.e. emergency money used when normal cash flow is disrupted, has been used. The lessons of their use may still be of interest to people today. You can get a piece of Hungarian emergency money for as little as a few hundred forints, but for the really special pieces, even auction houses offer substantial sums. To be precise, there's a wide range from a 550-forint ration coupon to a one-and-a-half million-forint German prisoner of war camp stamp with its own imprint.

The history of emergency money

Emergency money is a form of currency used in times of crisis, when the official money system fails. They served as a substitute and were often valid for a limited geographical area or for a limited period of time.

There certainly were 'emergencies' a long time ago

In the Middle Ages, when a war or economic crisis brought coin minting to a standstill, towns, guilds and landlords minted their own money. These were unofficial, but in the local economy, accepted means of keeping trade going, as people traded with each other, and thus ensuring the survival of the system.

There are not only old examples!

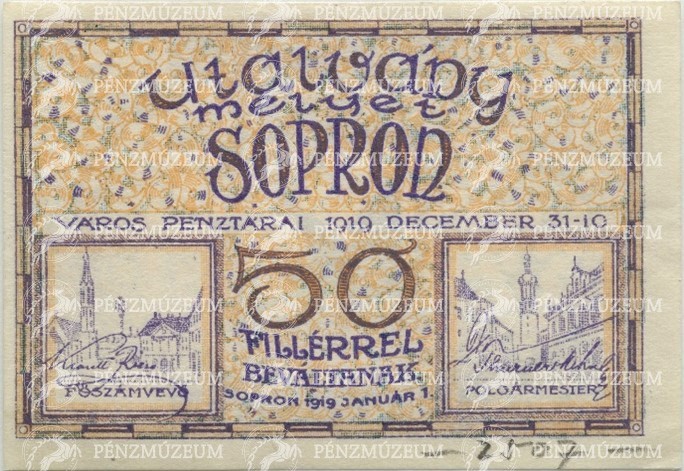

Even in the early 20th century there were emergencies, i.e. during the First World War, unofficial bills of exchange were introduced several times. The war economy in Germany and Austria also saw the emergence of so-called "Notgeld" emergency money, issued by towns and private companies. These were typically printed in small denominations and were quickly changed during periods of inflation.

Then came the Great Depression in 1929. In some US states, local emergency money was introduced when banks failed, and cash shortages developed.

Even prisoners of war had their own money

International conventions have regulated the situation of prisoners of war. In 1915, a meeting of the Red Cross representatives of the warring parties was convened in Stockholm, and a decision was taken to print camp money for internal use to improve the living conditions of prisoners. The prisoners were to be treated properly by their captors, including their food. If work was done by them, they were paid for it. Their cash had to be deposited, against which local camp money was issued. The text on some of the camp money also reads: THIS IS A PART OF THE MONEY DEPOSITED BY THE PRISONERS OF WAR AT THE CAMP. They received their money back when they were released, or when the camp authorities cashed in their camp money. This worked out well for the headquarters in several ways. On the one hand, they reduced the chances of escape by keeping legal tender in a depository, where prisoners had no access to it. On the other hand, it was in their interest that the prisoners should have as little contact as possible with the civilian population, especially not business contact. Therefore, the reason for issuing prisoner-of-war camp money was not so much a lack of money, but rather one of security, safety and prevention. It is no coincidence that higher denominations, 10 and 20 crowns, appear here alongside the pennies.

Prisoner of war camps typically ordered tickets to be printed in a printing house, with most printed by Globus Printing Company in Budapest. The drawings and texts were most often sent to the printing house by the camps, after they had assigned the task of designing to drawing teachers and artists. The printing house reproduced them by lithography, i.e. stone printing, typically using four or five colours. This was the first way the Somorja banknotes were produced. In Hungary, this type of token was issued, even several times, in the following settlements: Antalócz, Boldogasszony, Csót, Dunaszerdahely, Hajmáskér, Kenyérmező (Esztergom), Leibicz, Nagymegyer, Nezsider, Ostffyasszonyfa, Somorja, Sopronnyék and Zalaegerszeg for the crew, and Városszalónak and Léka for the prison officers. The number of camps was larger than this, but no records of the issue of camp money have survived there. The tickets could be Hungarian, German or bilingual, depending on the camp. The denominations were for 10, 20, 50 pennies, 1, 2, 5, 10 and 20 crowns, but it was rare for a camp to issue all denominations.

Hungarian prisoner of war camp coins were also produced abroad, for example in Russia, including Siberia.

Further news

All newsThank you for kind your understanding!

Thank you for your kind understanding!

The success of the HUNOR Program is now on display in the exhibition space

Thank you for kind your understanding!

Thank you for your kind understanding!

The success of the HUNOR Program is now on display in the exhibition space