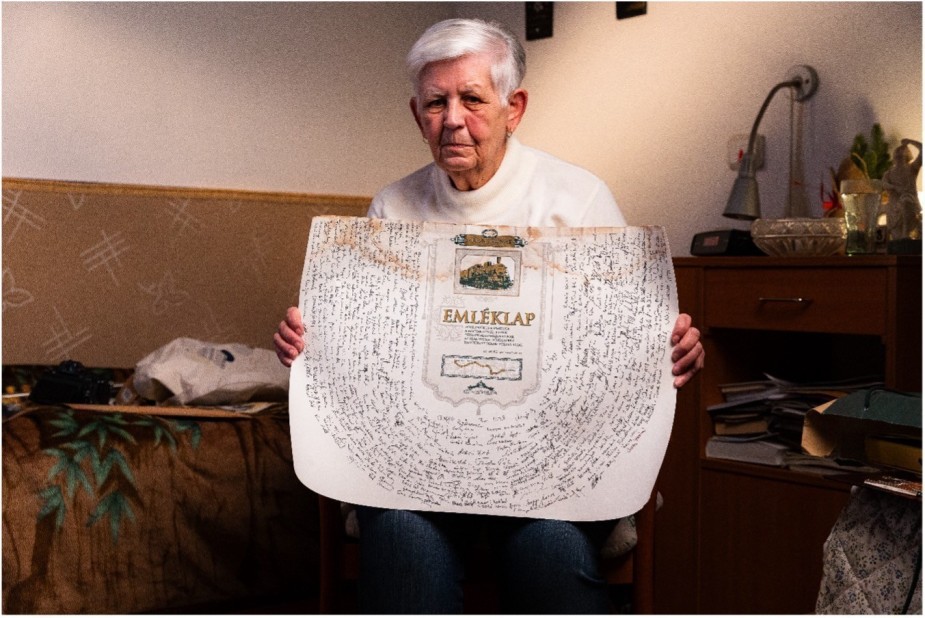

We imagined boarding the Gold Train with Tóth Ferencné Stark Mária, which set off for Austria from the railway station in Fertőboz 79 years ago, on the 23rd of January in 1945, and arrived in Spital on the 25th of January. Our subject not only contributed to the understanding of the Gold Train with physical memories, but also with her stories.

Oral history, or narrative history, is an important research method of the second half of the 20th century. It allows us to get first-hand information about a historical event, based on the accounts of eyewitnesses and survivors, from the subjective point of view of the individual. All we have to do is sit down and talk to those who are still with us. This is what we did in the case of the Gold Train, which set off 79 years ago on this very day, beginning one of the most adventurous, crime thriller-like journeys in Hungarian history.

Historical background

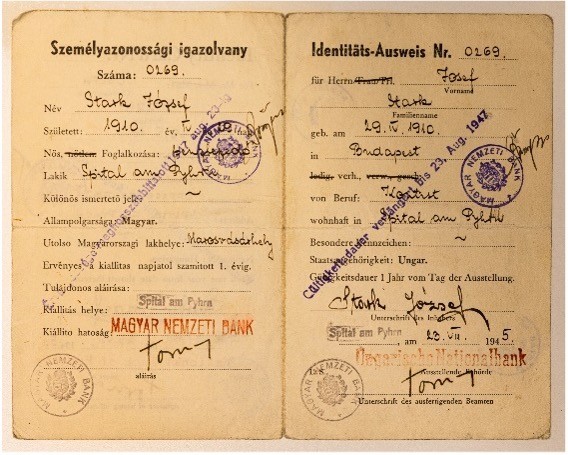

On the 19th of March in 1944, German troops invaded Hungary and on the 15th of October the Arrow Cross party took power. László Temesváry was appointed head of the Central Bank of Hungary and negotiations soon began to move Hungary's gold reserves westwards as the Soviets advanced. The German leadership's aim was to store the assets on the territory of the German Reich in several locations. If implemented, this would most likely have led to our national treasures falling into German hands for good, but the bank's employees resisted political pressure. In the December of 1944, the Gold Train set off from the bunker in Veszprém with the heroic employees of the central bank in order to deposit the 'nation's gold' in Spital after a cold and fearful Christmas in Fertőboz. The train rolled out of Fertőboz station on the 23rd of January and arrived in Spital on the 25th of January, where the treasures were stored in the crypt of the local Benedictine monastery. In the final days of the war, the administration again attempted to transport the valuables westwards. Negotiations were opened, but the German authorities only gave permission for the valuables to be transported, and only 30 of the staff of the central bank were allowed to accompany the treasures to Spital. In the tight situation, István Cottely decided to take a daring action: on the 2nd of May in 1945, two envoys left for Linz and Salzburg to meet the American army: Frigyes Tarnay and József Tuboly. They brought a letter and three telegrams with them, in which they described that about 600 employees of the Central Bank of Hungary and their families were currently in Spital am Phyrn with the entirety of the bank’s gold reserves. At the end of the telegrams, they asked that the bank and its employees be treated as an international and non-political organisation. US soldiers took the Hungarian gold reserves to Frankfurt am Main, where they were stored in the basement of the Deutsche Bank. Spital became an American occupation zone. In the June of 1946, negotiations took place in Washington to return the valuables held in Spital am Phyrn and Frankfurt am Main to Hungary. The Hungarian delegation was led by Prime Minister Ferenc Nagy. The US finally agreed to repatriate the Hungarian gold reserve and other valuables. This gold reserve was the collateral for the newly introduced forint. Mária Tóth Ferencné Stark, who was herself a passenger on the legendary train as a young child, shared her personal story with the Money Museum alongside her family photographs and artefacts.

Can you introduce yourself in a few words?

My name is Mária Tóth Ferencné Stark. My father was an employee of the Central Bank of Hungary, first working as a cashier in Budapest, then in Szeged and finally in Marosvásárhely. I was born in Marosvásárhely, the only daughter of my parents

How did you and your family end up on the Gold Train?

I was three months old when we had to leave Marosvásárhely. My father and his colleagues were escaping the approaching Russians while taking the bank ledgers in a lorry. My mother and I were first sent to Dés, and finally we met in Csesznek. But we weren't the only ones taken there, they were already collecting bank employees at the time. In Veszprém the valuables were hidden in a bunker under the castle, and we knew that we were going to Austria by train. We also knew what the cargo would be.

Did your parents know the danger they were putting themselves in?

Yes, they all knew. The Germans were in front of us, the Russians behind us, when the train left Fertőboz, the Russians had not yet arrived, but the bombing was already in full swing.

You spent the holidays in Fertőboz. Can you tell us about this period?

The children, including myself, were accommodated in first class carriages. The people of Fertőboz were very helpful all the time, they provided us with food, I don't know if they received any money. At Christmas they put up a Christmas tree for the children in the wagon. While we were waiting, we were bombed several times, so we hid in the wagons, we had nowhere else to go. The train was on a side track, in the forest, but we were still terrified of being hit. To this day I'm still scared of thunder.

What was your life like in Spital?

We were made very welcome by the locals, and while we were there, they were kind and helpful in every way. When we arrived by train, there was a good metre of snow and the bank employees, including my dad, were hauling 33 tonnes of gold and other valuables down to the basement of the monastery on sledges. Later, we were placed with a family, where my mother cooked and my father mended the bankers' clothes, as his original profession was tailor. They were well integrated, and so were the other families. They got used to it, that's how it is, you have to live there. What you can't change, you have to get used to.

Do you have family stories from your time there?

One of my memories has to do with beans. I didn't like green beans or green peas until I was thirty. Outside, green beans were grown on very tall stakes. I was two years old when one day my mother found me under one of those beans, I ate the raw beans. By the evening I had a fever of 40 degrees and my mother called the Americans for help. The doctor said if I made it to the morning, I would live. My other story is from 1964, when I went to Austria with an invitation letter. An aunt of mine was living there, and my uncle took me to Spital. I was two and a half years old when I came back from there and when I got out of the car, I asked my uncle that everything used to be pure white here, how come it's green now? Turns out I remembered a field of daffodils. There the daffodils grow freely, the many white daffodils stayed with me.

Did you have any contact with the people back home?

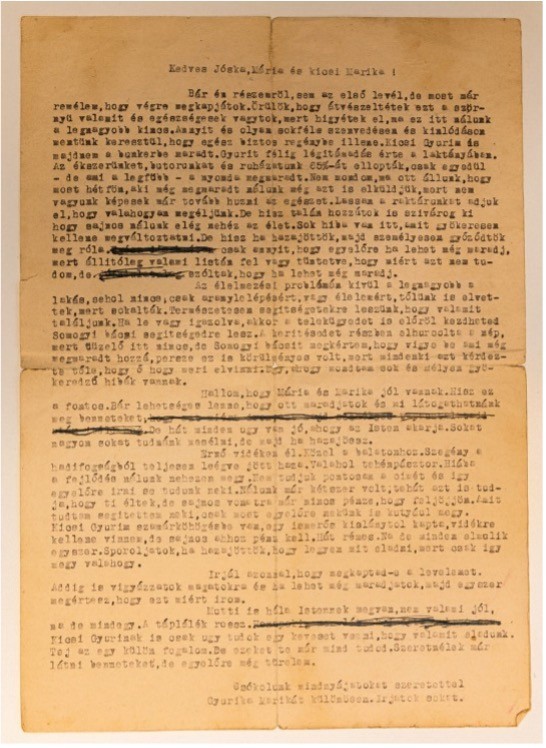

I have a letter, written by an aunt to my father, but it was censored. I offered this letter to the Money Museum.

Did you feel homesick while you were there?

We came home with the last shipment in October 1946. We already had our train tickets and boat tickets to Argentina, but the trip was cancelled because my father said, "I'm Hungarian, I want to go home".

Did you know what you were committing to by coming home?

We were not at all prepared for what was waiting for us at home. When we came home, my dad was transferred to Székesfehérvár, to the Central Bank of Hungary. Then in 1948 he was B-listed, called up to Budapest, and I went with him. As we came out of the bank, my father was terribly distraught. People he knew asked him what was wrong. He said he had been fired. I have no red book, and I was fired from the bank. This is a very sad memory for me. Then we had to move out of the flat where we had been living, we exchanged it for a caretaker's flat. My mum worked as a caretaker and my dad as a conductor for the Mávaut.

Have you personally suffered any discrimination?

We moved from Fehérvár to Sopron in 1957. After high school I wanted to go to university, but the headmistress in Sopron told me not to try, because I was a “westerner”, and to this day it hurts me that I was not allowed to go to university because I was sent abroad as a baby. But my father instilled in me that I was Hungarian, and that I belonged here.

Felhasznált irodalom:

Az MNB értékeinek háborús kálváriája. Tarnay Edgár visszaemlékezése. Forint 2000/5-6

B. J.: Spital am Pyhrn fél évszázad múltán. Forint 1997/5-6

B. J.: Tények az Aranyvonat(ok)ról. Forint 2000/1

Z.J: Arany a kriptában. Forint 1990/3-4 p. 15.

Emléktábla a kripta falán. Forint 1993/4-5

Cottely István: A magyar aranytartalék a második világháború viharában. Valóság. 1992.11

Garami Erika: Az „aranyvonat”, a monetáris aranykészlet története: 1944-1946. Éremtári Lapok, 2013. június. pp. 3-12.

Further news

All newsThank you for kind your understanding!

Thank you for your kind understanding!

The success of the HUNOR Program is now on display in the exhibition space

Thank you for kind your understanding!

Thank you for your kind understanding!

The success of the HUNOR Program is now on display in the exhibition space